Frequenter of Conventicles

Six months before the affray outside Kitchingman the merchant taylor’s house in York, yet another William Kitchingman was born in Kilburn in the North Riding. 1

William was the first child of Valentine K. He was not yet two when his mother Anne was buried in May 1643. Shortly afterwards, Valentine re-married. The family had moved the short distance to Thirkleby following the death of William’s grandfather (William alias Cleveland, depicted in an earlier blog). 2

William then disappeared from view until his father made his will in 1661. He received a legacy of £20. His half brothers Richard, John, Bryan, George and Andrew received £10 each in “full satisfaction of his portion and child part”. However, the tenant right of the farm in Thirkleby was left to Richard, with the residue of the estate to Richard and his mother Penelope. 3

William does not appear to have been disadvantaged, however. Copyhold property was not disposed of by will but through the manorial courts. In November 1662, he was admitted in the Archbishopric records to the moiety (half part) of West Park, Kilburn. This was a mixed arable, pasture and meadow farm of 59 acres, which had belonged to his grandfather. Significantly, William was described as a cloth dresser (a brief account of the Yorkshire wool industry in will be given in another blog). 4

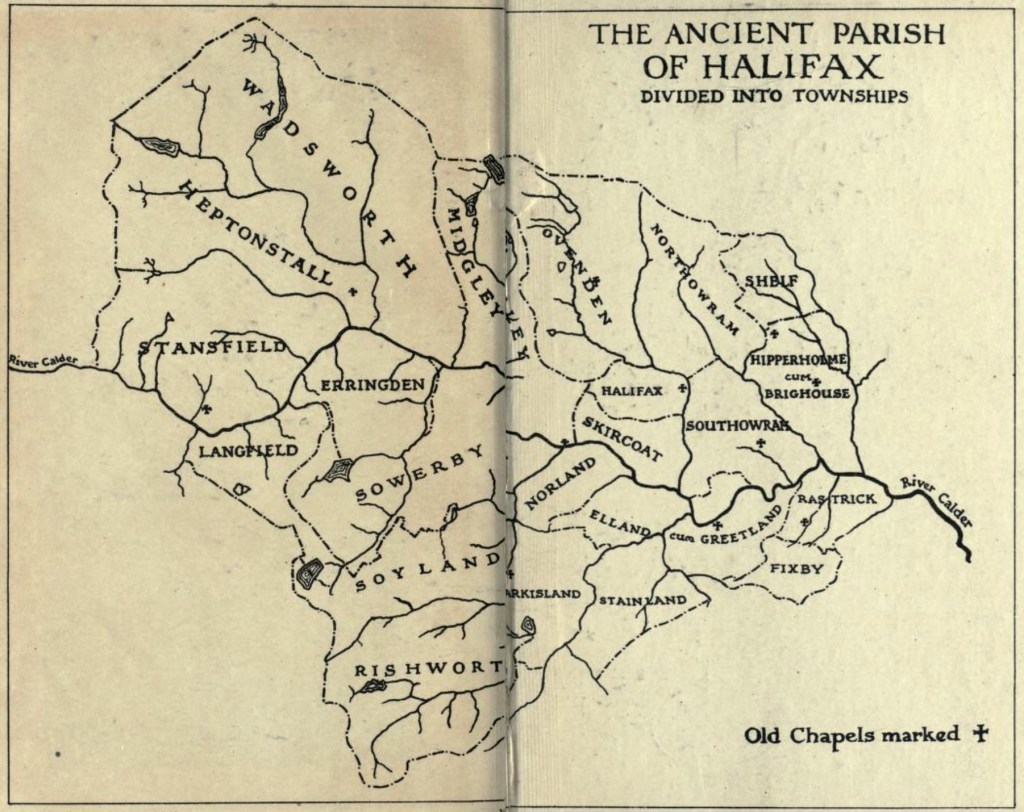

It is not clear if William was still resident in Kilburn at the time of his inheritance. However, by 1668, when he married Sarah Coulborne of Prestwich in Lancashire, he was a clothier of Halifax. Four years later, he was taxed on a house with three hearths in Ovenden, one of Halifax’s townships. 5

Map by T. Broadbent in T. W Hanson, The Story of Old Halifax, (Halifax, 1920)

Life in Halifax

There is nothing in William’s early life to suggest that the family did not conform to the established Church. For example, his half brother Richard went on to become churchwarden in Thirkleby and Chief Constable for the wapentake of Birdforth. These roles were, however, explicitly excluded from being subject to the Test Act, requiring an oath of allegiance to the Crown and receiving the Anglican communion. 6

For William, however, things changed in Halifax.

This was a huge parish, seventeen by eleven miles across, divided into twenty three different townships. Part of the clothing district of the Yorkshire West Riding, it had been a stronghold of Protestant non-conformity since the sixteenth century and through the Civil War. 7

After the Restoration of Charles II, the ebb and flow of religious toleration and persecution can be seen in the life of Oliver Heywood, the Presbyterian Minister.

In the years following the Act of Uniformity of 1662, which mandated a return to the Book of Common Prayer, he was excommunicated from the Church of England, put out of his living at Coley Chapel and imprisoned for a year in York Castle. As an itinerant preacher, Heywood continued to preach, baptise and hold prayer meetings or conventicles in private houses in Halifax and further afield. His diaries record two visits to William K’s house in Skircoat Green. 8

Was William Kitchingman then a “Dissenter from and disaffected to the Church of England” and a “frequenter of Conventicles”? This was the allegation in a Cause brought before the Archbishop’s Consistory Court in 1689. 9

The case arose from a disputed election to the position of Lecturer, who would preach sermons on Sunday afternoons in Halifax parish.

‘Reverend Oliver Heywood’, Presbyterian minister of Coley Chapel,

Gustavus Ellinthorpe Sintszenig, Mansfield College, Oxford.

William was a witness and protagonist, one of eight men, of “good Estates and repute”, who canvassed hundreds of named votes for the favoured candidate of the parishioners’ and Vicar.

In opposition, Simon Sterne and his faction claimed that the election was invalid. Only the “better and more substantial sort of persons”, able to contribute to the maintenance of the Lecturer, should have been entitled to vote. Many of those voting were ineligible on account of being “wives voting against their husband’s will, children, servants, apprentices, poor and indigent people…and some really dead”. Moreover, even many of those legally entitled to vote should be disbarred on religious grounds as Dissenters.

As Samuel Thomas has concluded in his book on the religious community of Halifax, “what makes these accusations interesting is that they seem to have been true”. He argues that this stems from the inclusive views of Heywood and his followers. They understood, the congregation of the godly in the widest sense, embracing those who could only make a token contribution to parish funds and irrespective of denominational boundaries. It was certainly the case that parishioners could both attend Anglican services and go “sermon gadding” with dissenting preachers. 10

While it might be tempting to see William as an early supporter of universal suffrage, a simpler reading may be that this was a brazen attempt to pack the vote in favour of a candidate of their religious preference. In any event, Simon Sterne did not get his way and a different Curate to either of the original candidates was appointed to the satisfaction of the majority of the parishioners.

As with anti-Popery in York on the eve of the Civil War, it may be that this local dispute reflects the national anxieties which led to the Glorious Revolution. Sterne was a gentleman, Justice of the Peace and third son of a former Archbishop of York. Perhaps he expected the middling sort to pay him due deference? As a recent incomer to the town, he seems to have underestimated the fierce independence of Halifax’s yeoman clothiers and was out of step with the times. 11

A year before the case, the Act of Toleration had granted religious freedom outside of the Church of England. It permitted many Protestant non-conformists to establish their own places of worship. One example of this was Northgate-End Chapel in Halifax, with the first sermon preached by Heywood in 1696. William K was one of the founding trustees. By 1706, other trustees included the ministers Nathaniel Priestley and Ely Dawson (later left annuities by William), as well as James Greame (husband of William’s daughter Ann), and members of the Stansfield and Priestley families also related by marriage. 12

William may well have been a “frequenter of conventicles” but it did not harm his prospects. He lived until the old age of 79. All five of his surviving daughters went on to make good marriages, based on the shared bonds of community, business and religion. When he died in 1719, he was described as “very rich”. The validity of that judgement will be the subject of a further blog. 13

References

- Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Kilburn Parish Register, 17 November 1641.

- Kitchingman Memorial, Halifax St John. The Non-Conformist Register,

- Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Prerogative Court of York Wills, Vol. 46, folio 54, Valentine Kitchingman of Little Thirkleby, dated 18 January 1661, proved 24 October 1663.

- Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive: CC Ab.5/3; Archbishop Sharpe’s MSS, Vol. 2, 1692-93. The Kilburn records with leases for three lives give ages and relationships, so are invaluable in untangling the various Kitchingmans with identical first names from 1621 until well into the eighteenth century.

- Society of Genealogists, Boyd’s Marriage Index 1538-1850, William Kitchinman and Sara Coulborn of Prestwich Lancashire. J. W. Clay (ed.), Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series, Vol 43, Paver’s Marriage Licences: Vol II, (1911), p. 122: William Kitchingman, clothier, 26, Halifax; Sarah Coulborne, spinster, 21, Prestwich.

Hearth Tax Digital Three quarters of households in Ovenden had two hearths or less in 1672. William K’s three hearths place him among the middling sort, with 21% of households having three to four hearths. Very few houses had more than this, reflecting the absence of resident gentry in the Halifax area. - Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Bishop’s Transcripts. Thirkleby, 1670.

J. C. Atkinson (ed.), Quarter Sessions Records, Vol. VII, (London, 1889), 12 July 1692, p. 129, https://archive.org/details/cu31924024238069/page/n155/mode/2up?q=kitchingman

Test At 1672, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp782-785 - D Hey, ‘The West Riding in the Late Seventeenth Century’, D. Hey et al, Yorkshire West Riding Hearth Tax Assessment Lady Day 1672, (London, 2007).

S. S. Thomas, Creating Communities in Restoration England: Parish and Congregation in Oliver Heywood’s Halifax, (Netherlands, 2013) pp. 11-16. - Act of Uniformity 1662, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp364-370.

J. H Turner (ed.), The Rev. Oliver Heywood, B.A., 1630-1702; His Autobiography, Diaries, Anecdote and Event Books, Vol. 2, (Brighouse, 1882). pp. 80, 97. Heywood’s Diary in 1678 records two visits to William K at his house in Skircoat, once leaving his wife there with friends.

See also Conventicles Acts of 1664 and 1670, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp516-520 and https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp648-651, Five Mile Act 1665 https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/p575, Declaration of Indulgence 1672 https://openworks.wooster.edu/notestein/29/.

J. H. Turner, Biographica Halifaxiensis, Vol I, (Brighouse 1883), pp. 95-97, provides a useful introduction to Heywood’s life and works, https://archive.org/details/biographiahalifa00turnrich/page/92/mode/2up

See also W. J. Sheils, ‘Oliver Heywood and his Congregation’, Studies in Church History, 23, 261-277, (Cambridge, 1986), http://Studies in Church History, 23, 261-277 and

J. Hunter, The Rise of the Old Dissent, (London, 1842), https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=_OGglVXfNi4C&printsec=titlepage&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false - Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Cause Papers, CP.H.4219 17 October 1690 – 23 April 1691 https://www.dhi.ac.uk/causepapers/causepaper.jsp?id=100854 and CP.H. 4220 17 October 1690 – 28 November 1690 https://www.dhi.ac.uk/causepapers/causepaper.jsp?id=100855.

- S. S. Thomas, Creating Communities in Restoration England: Parish and Congregation in Oliver Heywood’s Halifax, (Netherlands, 2013) pp. 97-119. In his unpublished PhD. thesis, ‘Individuals and Communities: Religious Life in Revolutionary Halifax’, (Washington University, 2003),

pp. 220-221, https://www.proquest.com/openview/0400030599c5f42b9cb64537bef01c97/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y, Thomas states that “the charge of nonconformity is the most difficult to substantiate against William Kitchingman”. However, he seems to have omitted a second visit recorded by Heywood with his wife on 24 June 1679 to “Jo. Kitchingmans at Skircote where I left her with friends” (Turner, op. cit., p.275) and not to have been aware of Kitchingman’s role in the founding of Northgate End Chapel. Additional inference may be drawn from William’s half brother George, an Ovenden dyer, voting for the preferred candidate (CP.H.4219 op. cit). William’s wife may also have come from a dissenting family – on her death Heywood’s successor recorded her as “my kinswoman”. - W. Calverley, ‘Memorandum Book of Sir Walter Calverley Bart.’, in in C. Jackson (ed.), Yorkshire Diaries and Autobiographies in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries‘, (Durham, 1886), p.80, Simon Sterne Esq. JP bought Woodhouse in Skircoat for £1800 in 1688. https://archive.org/details/yorkshirediarie00marggoog/page/n94/mode/1up?q=sterne.

Sterne was the grandfather of the novelist Laurence Sterne (1713-1768), who went to school in Halifax. J. W. Clay, ‘The Sterne Family, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol. 21, (1911),

pp. 91-107, https://archive.org/details/YAJ021/page/91/mode/1up?q=sterne

There is a considerable literature on tolerance and persecution in the early modern period. See the University of Cambridge reading list, A. Walsham, ‘Persecution and Toleration in Britain 1400-1700’, https://www.hist.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/specified_paper_-20-_persecution_and_toleration_bibliography_and_course_guide_2020-1.pdf. - The Toleration Act of 1689 allowed most Protestant non-conformists to worship openly, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol6/pp74-76.

F. E. Millson, A Bicentenary Memorial: Two Hundred Years of the Northgate-End Chapel, Halifax, (Halifax, 1886), pp. 5, 9, 37. https://archive.org/details/bicentenarymemor0000mill/mode/2up

J. Stansfeld, History of the Family of Stansfeld or Stansfield Family, (Halifax, 1885), pp. 405-406, https://archive.org/details/historyoffamilyo00stan - Anne Kitchingman married James Greame in 1691, a clothier and son of Mr Henry Greame, gentleman, Borthwick Institute for Archives, Diocesan Archives, Archbishop of York Marriage Licences Index 1613-1839.

Elizabeth Kitchingman married first Thomas Priestley, gentleman in 1693 and then Mr. James Stansfield of Bowood in 1706, J. H. Turner (ed.), The Non-Conformist Register, (Brighouse, 1881), p.48, p199, https://archive.org/details/nonconformistreg00byuheyw/mode/2up

Sarah Kitchingman married Nathaniel Jenkinson of Manchester in 1698, Borthwick Institute for Archives, Diocesan Archives, Bishop’s Transcripts for Halifax.

Mary Kitchingman married Joshua Firth of Bradford, Dr of Physick in 1703, J. H. Turner, op. cit.,

p. 198.

Dorothy Kitchingman married Mr Matthew Blyford of Norwich, woollen draper in 1703.

“Mr William Kitchingman of Skircote, died June 6, very rich, aged about 79”, J. H. Turner, op. cit., p.278

Leave a comment