Died, very rich?

The Non-Conformist or Northowram Register, as it has become known, does not merely preserve the bare bones of baptisms, marriages and burials between 1644 and 1743. 1

The Presbyterian minister Oliver Heywood and his successor Thomas Dickenson occasionally added pithy comments that help illuminate the lives of their congregation in Halifax (and some further afield).

Halifax St John, including William 1641-1719.

One example of this came with the death of Mr. William Kitchingman of Skircoat, previously encountered in the Frequenter of Conventicles blog. The entry for 6 June 1719 states that William died “very rich”. 2

A search of the Register reveals at least 28 other men and women who received the same label, along with 37 merely “rich” and one “vastly rich”. These seem surprisingly large numbers, even over the course of a century, so warrant further investigation.

What did Heywood and Dickenson count as “very rich”? It was only quantified in one instance in the Register, with the death in about 1725 of Mr. Joseph Beever of Sandal Magna who “made of will of Ten thousand pound”. Beever was a dyer of New Miller Dam and had been Chief Constable of the wapentake of Agrigg. His will includes legacies of £1000 each to his two daughters, as well as extensive bequests of property to his three sons. 3

William Kitchingman did not start life particularly rich. In 1661, he inherited £20 from his father Valentine of Thirkleby, along with the copyhold of a 59 acre farm in Kilburn in the North Riding, which he retained throughout his life. 4

By 1672, he was taxed on a house in Ovenden, one of Halifax’s townships. Three quarters of households in Ovenden had two hearths or less. William’s three hearths placed him among the middling sort, with 21% of households having three to four hearths. Only seven houses had more than this. 5

By the time William left a will, dated 15 May 1718, his circumstances had improved considerably. The will detailed a substantial and widespread estate including:

- the messuage and tenement “wherein I now dwell” in Skircoat;

- another messuage and tenement in Skircoat, commonly called Boy Farm, in the occupation of a tenant;

- West Park in Kilburn, the farm inherited from his father;

- a tenanted messuage called Nuttall Tenement in Heywood in the parish of Bury (bought in 1697);

- a messuage known as Shipley’s tenement in Failsworth, which William had bought from his son-in-law Nathaniel Jenkinson;

- a sixteenth share of a ship called ‘Mary & Martha’ of Whitby. 6

(1641-1712), by Sir Peter Lely.

In addition to these properties, William records two debts or “tallies”owed by Lord Ranelagh, the Paymaster General of the King’s Horse. The latter were almost certainly desperate debts, as the disgraced peer had been convicted for “high crimes and misdemeanours”in public office and died “very poor and needy” in 1712. 7

Having no surviving sons, William appointed his grandson William Gream as the sole executor and residuary beneficiary of the will. Out of the estate he was expected to pay the following:

- annuities of £6, £5 and £8 respectively to William K’s surviving daughters Ann Gream, Elizabeth Stansfield and Sarah Jenkinson;

- £100 to James Gream according to covenants of marriage with Ann;

- £10 each to grandchildren James, John, Sarah and Ann Gream;

- £500 to grandson William Jenkinson along with Shipley’s Tenement in Failsworth;

- £100 to granddaughter Elizabeth Jenkinson and £60 to granddaughter Mary Firth;

- annuities of £2 each to the Presbyterian ministers Nathaniel Priestley and Eli Dawson;

- a token £1 each to William K’s half brothers George and Bryan (of the Halifax townships of Ovenden and Sowerby) and to cousin Valentine K of Thirkleby (in fact the son of William’s half brother Richard, so a nephew).

So, at a minimum, William left cash legacies of £803 and annuities of £23. One comparison is provided by John Smail’s analysis of 131 Halifax wills in the period 1689-1719. He notes that only twelve men left bequests of over £500, of which only three were in the textile industry or professions. It is unlikely that William’s will would have been included, as it was not proven until 1761 in Canterbury rather than York. Nonetheless, this would place William in the top ten per cent of will makers, who themselves were mainly confined to the better off. 8

William survived until his late seventies, so any assessment of his wealth needs to take into account earlier lifetime distributions. When his daughter Anne married James Greame in 1691, a complex settlement was put in place with “her dowery £500”. William’s four other daughters – Elizabeth, Sarah, Mary and Dorothy – also made good matches. Assuming that they received similar portions on marriage, that would have added a further £2500 to his net worth. 9

Relative values

Perceptions of wealth are, of course, relative.

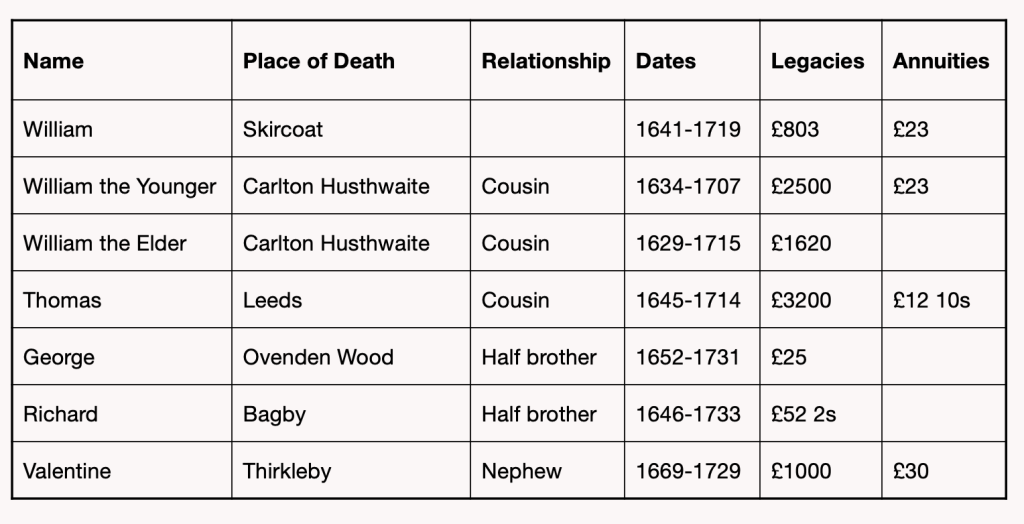

The table below shows the value of legacies left by William’s kin, taken from some of the surprisingly high number of Kitchingman wills that survive from this period. 10

This is a limited comparison, as it neither accounts for the value of real estate nor personal property (probate inventories have not survived). It does suggest, however, that William had prospered to a greater degree than his half brother George but rather less well than his Leeds and Carlton cousins. It may be that his half brother Richard had passed on most of his wealth before reaching the age of 89. Compared to others in his family, it is clear that William was at the least comfortably off.

In an area like Halifax, where there were few resident gentry, even moderately well-off yeoman clothiers might have been seen as rich. This might be particularly so for non-conformist ministers with modest livings. Heywood, for example, had only £77 a year from his congregation, albeit with further income from his inherited lands. 11

In surviving records, William was variously described as a cloth dresser, clothier, merchant, Mr., gent, and yeoman (the title he gave himself in his will). These titles were not mutually exclusive and may reflect changes in occupation/status over time. This ambiguity of social standing is underplayed in John Smail’s account of the middling sort at the end of the seventeenth century. Drawing on evidence from probate inventories, he argues that,

“Put simply, richer people did not own better chairs, merely they owned more of them.” 12

He goes on to contrast relatively egalitarian clothier’s houses, which incorporated workshops for the domestic production system, with the very separate mansions built by mid-eighteenth century manufacturers – a visible expression of middle class consciousness.

One of the case studies Smail cites is the Stansfield family, into which William’s daughter Elizabeth married after the death of her first husband. James and Elizabeth Stansfield bought Old Field House; in 1749, their grandson George built the Palladian mansion next door. While this clearly signifies a change in material culture, this was at least partly due to increasing business scale – something only made possible by the cumulative success of preceding generations. This supports a much more gradualist view of change than Smail’s thesis suggests. 13

Humphrey Bolton, Old Field House, Upper Field House Lane, Sowerby CC BY-SA 2.0

Real treasure

For the family historian, the real treasure in William’s story lies in what it reveals about kinship ties across time and space.

William and Sarah had seven children in all. William and Martha died in childhood, as the memorial above shows. Ann, Elizabeth, Sarah, Mary and Dorothy survived until adulthood, all marrying in their early twenties. 14

The provision for his daughters, son-in-laws and grandchildren in his will is unsurprising.

The recognition of his half brothers, George and Bryan, is more unusual; perhaps reflecting William’s role in helping establish themselves as young men in Halifax?

By also remembering his nephew Valentine, William demonstrated that the connection with his family in Thirkleby in the North Riding remained intact over 50 years after leaving to seek his fortune in Halifax.

Kinship connections could be a matter of business as well as affect, as shown in his share in the ship of which “one Wm. Kitchingman mariner goes master”. This namesake was the son of yet another half brother, John (1649-88). He had made the journey from Thirkleby to Whitby to found a dynasty of master mariners. Their story will be taken up in a later blog. 15

References

- J. H Turner (ed.), The Non-Conformist Register, (Brighouse, 1881), https://archive.org/details/nonconformistreg00byuheyw/page/n9/mode/1up?view=theater

- J. H. Turner, op. cit, p.278.

- J. H. Turner, op. cit, p.293.

West Yorkshire Archive Service, Wakefield Quarter Sessions 1712-1720, 26 April 1715, p. 93.

Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Prerogative Court of York Wills, Vol. 78, folio 191, Joseph Beever of New Miller Dam, dated 7 August 1725. - Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Prerogative Court of York Wills, Vol. 46, folio 54, Valentine Kitchingman of Little Thirkleby, dated 18 January 1661,

proved 24 October 1663.

Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive: CC Ab.5/3; Archbishop Sharpe’s MSS, Vol. 2, 1692-93. The Kilburn records with leases for three lives give ages and relationships, so are invaluable in untangling the various Kitchingmans with identical first names from 1621 until well into the eighteenth century. - Hearth Tax Digital

R. A. H. Bennett, ‘Enforcing the Law in Revolutionary Yorkshire, c.1640-1660’, (Kings College London, unpublished PhD. thesis, 1987), pp. includes a useful analysis of the social and occupational structure of Halifax based on 1664 hearth tax returns and marriage records,

pp. 59-67, https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/2934849/283797.pdf

See also M. Shand, ‘Mapping the Hearth Tax’, (2022) for how Halifax compared to other areas

https://hearthtax.files.wordpress.com/2022/05/england-3-over-hearth-map.jpg - National Archives, PROB 11/869/223, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, William Kitchingman, Skircoate, proved 9 October 1761. Probate was granted to Isaac Clegg, the surviving executor of William Greame. It may be that the delay of over 40 years was due to lack of awareness of the need to prove in Canterbury, as property was held in more than one province.

- J. Bergin, ‘Richard Jones (1641-1712), First Earl of Ranelagh’, Dictionary of Irish Biography, https://www.dib.ie/biography/jones-richard-a4337. K. Howard, The Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. X, (Oxford 1921), pp. 1042-1043. Were these unpaid debts for cloth for the army?

- J. Smail, ‘The Stansfields of Halifax: A Case Study of the Making of the Middle Class’, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, Vol. 24, 1, (Spring 1992), p. 33, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4051241.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A0156b4b0a5775b40cdefaffd9ca0cc0f&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=search-results

- See T. Arkell et al, When Death Do Us Part, (Oxford, 2004) for an introduction to the interpretation of wills and other probate records.

Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, YAS/MD213, Folder III, Bond or Covenant 14 Sep 1691 about marriage of James Greame & Anne Kitchingman…”her dowery £500″;

West Yorkshire Archive Service, WYL323/93, Conveyance dated 1691 from Henry Greame of Southowram to Henry Greame his son and George Kitchingman of Ovenden Wood.

J. Priestley, ‘Memoirs of the Priestley Family’, (1696), in C. Jackson (ed.), Yorkshire Diaries and Autobiographies in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries‘, (Durham, 1886), p.25, describes William as a merchant in bond of 3 October 1694, on marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to Thomas Priestley, “her fortune £400”. https://archive.org/details/yorkshirediarie00marggoog/page/n39/mode/1up?q=kitchingman - Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, York Peculiars Probate Index: Box 001, Set055, William Kitchingman the Younger, dated 15 March 1706;

Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, York Diocesan Archive, Prerogative Court of York Wills: ; Vol. 73, folio 104 William Kitchingman the Elder dated 6 February 1718; Vol. 17, folio 52, Thomas Kitchingman, dated 28 August 1713; Vol. 82, folio 48, George Kitchingman dated 18 April 1730; Vol 83, folio 484, Richard Kitchingman dated January 1734; Vol 81, folio 604, Valentine Kitchingman dated 16 October 1730. - S. S. Thomas, ‘Individuals and Communities: Religious Life in Revolutionary Halifax’, (Washington University, 2003), p. 140,

https://www.proquest.com/openview/0400030599c5f42b9cb64537bef01c97/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y - J. Smail, The Origins of Middle-Class Culture: Halifax, Yorkshire, 1660-1780, (Ithaca, 1994),

pp. 37-4. - J. Smail, ibid, pp. 107-113;

J. Smail, ‘The Stansfields of Halifax: A Case Study of the Making of the Middle Class’, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, Vol. 24, 1, (Spring 1992), p. 33, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4051241.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A0156b4b0a5775b40cdefaffd9ca0cc0f&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=search-results

H. P. Kendall, ‘The Fieldhouses in Sowerby’, Halifax Antiquarian Society, Transactions, (Halifax, February 1921,). p. 28

J. Stansfeld, History of the Family of Stansfeld or Stansfield in the Parish of Halifax, (Leeds, 1885), pp. 209-210 - Kitchingman Memorial, Rokeby Chapel, Halifax St John.

Anne Kitchingman married James Greame in 1691, a clothier and son of Mr Henry Greame, gentleman, Borthwick Institute for Archives, Diocesan Archives, Archbishop of York Marriage Licences Index 1613-1839.

Elizabeth Kitchingman married first Thomas Priestley, gentleman in 1693 and then Mr. James Stansfield of Bowood in 1706, J. H. Turner (ed.), The Non-Conformist Register, (Brighouse, 1881), p.48, p199, https://archive.org/details/nonconformistreg00byuheyw/mode/2up

Sarah Kitchingman married Nathaniel Jenkinson of Manchester in 1698, Borthwick Institute for Archives, Diocesan Archives, Bishop’s Transcripts for Halifax.

Mary Kitchingman married Joshua Firth of Bradford, Dr of Physick in 1703, J. H. Turner, op. cit.,

p. 198.

Dorothy Kitchingman married Mr Matthew Blyford of Norwich, woollen draper in 1703, Borthwick Institute for Archives, Diocesan Archives, Bishop’s Transcripts for Halifax.

Both died young and this led to parallel Chancery Court cases of Blyford v Kitchingman and Kitchingman v Blyford between William K and Matthew’s surviving siblings.: National Archives,

DEL 2/11, 1716; DEL 1/452/971 1716; C 11/2349/35 and PROB 18/34/39 1715. - North Yorkshire County Record Office, Baptisms, marriages & burials:

Thirkleby, PR/TK 1/1,p. 18, John son of Valentine Kitchingman baptised 18 May 1649;

Whitby St Mary the Virgin, N-PR-WH1-3: p.88, John Kitchingman married Mary Hope 15 April 1680; p. 132, buried 1 January 1689, “Mr. Mariner”; p. 19, William son of John Kitchingman baptised 30 August 1684.

Leave a comment